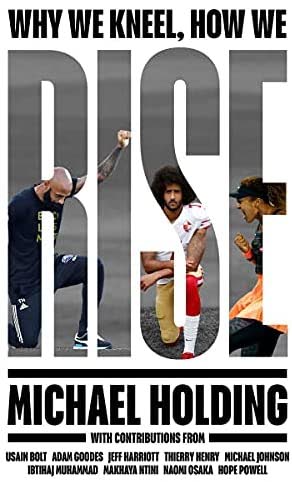

Why We Kneel, How We Rise is the title of the newest book by Michael Holding, the great fast bowler of the golden years of West Indies cricket in the 1980s and 1990s.

The book appeared earlier this year and is published in the UK by a leading publishing house, Simon & Schuster. It is guaranteed to be read by any thinking person in the world who is sensitive to current affairs, especially sports enthusiasts and those who understand that we must continue to deal with the global fallout from the George Floyd murder and the coming of #BlackLivesMatter.

Michael Holding on his own is worth reading for his clarity of vision, great facility with the English language, his enviable capacity to articulate the finer points of the beautiful game of cricket, his courage to tell it how it is and his independence of mind.

In this new book, though, he adds more star value by including contributions from the intriguingly iconoclastic Naomi Osaka of tennis, Thierry Henry of the unforgettable days of Arsenal’s domination of the football pitch and beyond, the untouchable, lightning sprinter Usain Bolt, Aboriginal footballing icon Adam Goodes, double 1996 Olympic gold medallist Michael Johnson, the first hijab-wearing Olympian, Ibtihaj Muhammad, legendary cricketing South African fast bowler Makhaya Ntini, and Hope Powell, the first black coach of an English national sporting team when she became England women’s football manager in 1998. Together they weave a compelling account of what it is like to be great but also a victim of racial derision and its effect. It’s a story of our societies and our world.

Holding, a bold man, hardly given to bursting into tears, was completely overcome by grief and powerful emotion at the George Floyd killing. It gave rise to this new title, which has been a Sunday Times bestseller. He had never said anything about the racism he had endured throughout his career – most victims put up and shut up – but he could not restrain himself when one day in September 2020 the rain delayed play and cricket talk between on-air commentators became race talk, live on Sky Sports television. It was a few weeks after the video recording of George Floyd begging for his life as a white policeman snuffed it out of him by unrelentingly pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck.

Asked to comment further by Sky News, Holding, a man who enjoyed near-worldwide trust and respect for his integrity, let rip on the scourge that is racism for those who are its victims. Holding’s surprising utterances went viral and added succour to the fast-growing movement against a reality that many unconscious perpetrators reject. It led to the scales falling from the eyes of many who had never really engaged with the subject, believing racism to be somebody else’s problem, or something black people should “get over.”

I recommend this book for a condensed and precise history of how we got to where we are now, highlighting black achievement across diverse professions and disciplines and sharing insights and different perspectives on matters such as positive discrimination, and the pros and cons of mandating for equal representation.

It was fascinating to watch the fulsomeness of the BBC’s coverage last week of Barbados’s move to republican statehood and to regard the symbolism of the severing of formal colonial ties with Britain. Barbadians, citizens of the first and most successful British slave colony, who still live with many of the visible vestiges of that past, heard the future King of England call slavery an appalling atrocity and an indelible stain on history, exactly the words he previously used in Ghana but never before voiced in the Caribbean.

Britain exported 3.1 million Africans to be enslaved in the Americas for nearly two centuries. British journalists, as much as The Firm, as Queen Elizabeth refers to the business of being the royal family, knew what was expected at this moment and especially in Barbados, which was the very backbone of the shameful trade.

Acknowledgement is important, but with the supposed and enduring inferiority and otherness of the offspring of those slaves so well ingrained in the minds of most of the world, is there really a chance to make black people’s lives better?

Well, if money really talks. Holding cites Nike donating US$40 million to support black communities in the US, Apple putting in US$100 million, Amazon US$27 million and Sony US$100 million towards racial equality initiatives, and that is in addition to JP Morgan committing US$30 billion between 2020 and2025 to build black businesses, fund community projects and affordable housing. Citibank and Bank of America have each pledged US$1 billion for the same purpose.

These are hefty investments for long-term effects and must make financial sense to the donors. They are not giveaways, just like freedom from slavery had a big dollar sign on it, and had little to do with mankind changing heart.

But I agree with Holding and his contributors that a long period of re-education is needed, as much as continuing to kneel in order to rise. Five centuries of acculturation cannot be undone in a jiffy.